The Berlin-based Kiwi creates with waste for the benefit of people and the planet.

It’s a gigantic geographical and cultural leap from Auckland’s leafy Titirangi to the gritty buzz of Berlin, but material designer Sophie Rowley’s calling — turning waste into designer objects — would be much appreciated in her childhood stomping ground. Sophie, who lives in an apartment in the German city’s Prenzlauer Berg area, takes a global view of her profession. That’s not surprising — she moved with her family to Germany in her high-school years, studied textile design in Berlin, then embarked on a master’s course in London, where she experimented with new materials across various mediums and design fields. A stint at British artist Faye Toogood’s studio was followed by an eye-opening time at an innovation hub in Mumbai, India. Today, the development of her own ideas sees her transforming ‘worthless’ materials into covetable products.

Sophie, what exactly is a material designer? Basically, I work with soft and solid materials and am not restricted by an expected outcome or to an industry in which the object, surface or design should fit. For example, I often get asked by companies to find ideas for recycling their production waste. It’s helpful that I have such a diverse background as I can think across borders. Sometimes, a new recycled material would be more useful in a different industry.

Why focus on sustainability? In times of declining natural resources, we’ll be increasingly challenged to find ways of working with non-virgin materials, rather than extracting more of our planet’s finite goods. Waste is our only growing resource.

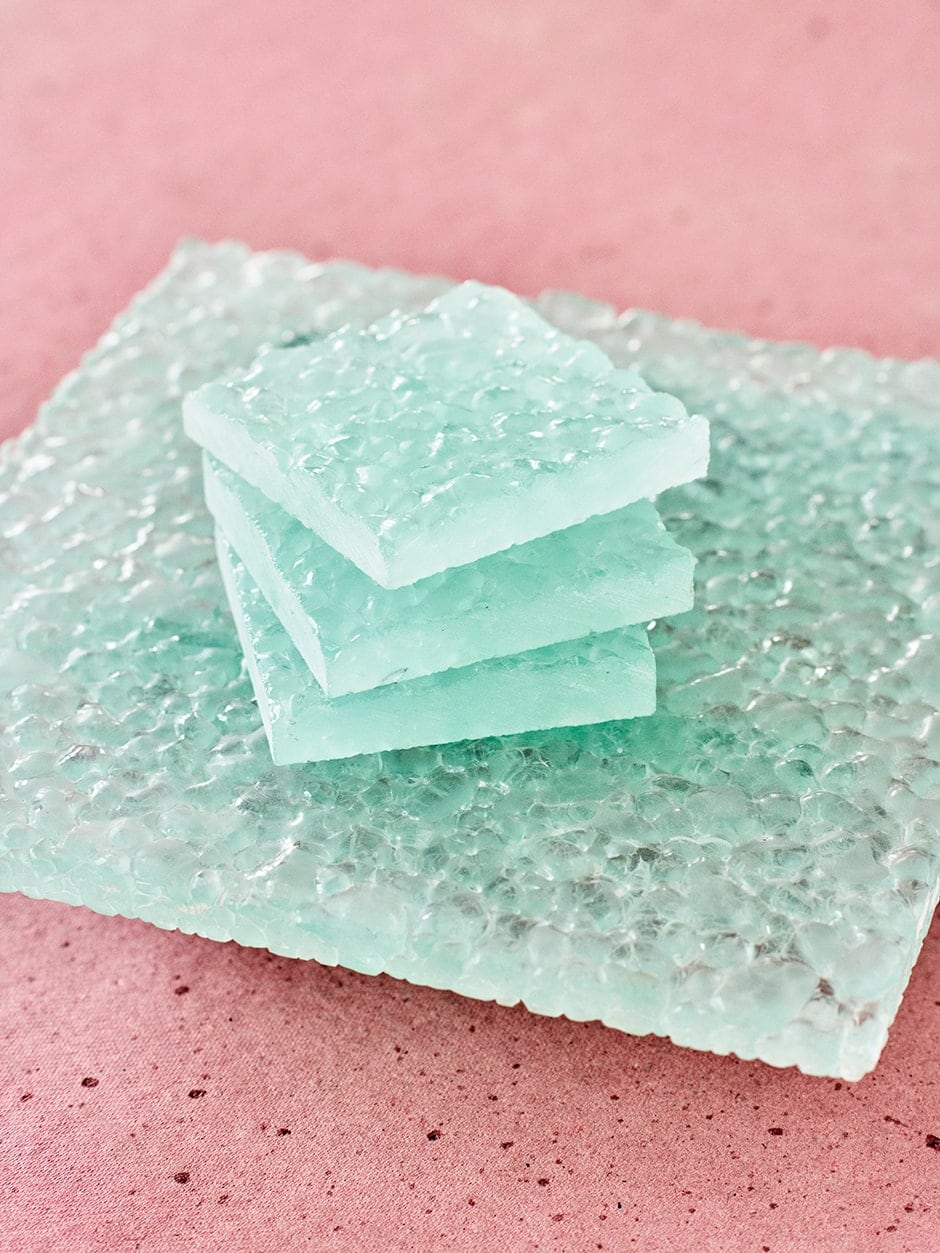

In the past, many recycled materials were developed by engineers, so they were driven by scalability and practicality, rather than aesthetics. For me, aesthetics play an important role; even if a material is recycled, it has to be desirable. I like the challenge of working on something ‘ugly’ until it transforms. I aim to prove that it’s not necessarily the material source that decides value, but how we work with that material. Through melting down polystyrene, for instance, you might create some really cool effects that you can’t achieve with a natural material.

We love your Bahia Denim side tables and stools — tell us about those. Bahia Denim is named after the Brazilian blue marble Azul Bahia and gives the visual illusion of marble. It’s made from post-consumer denim waste; the cut pieces are layered, adhered and carved to create intricate patterns, the variation in size, shade, colour and texture making the designs unique. It was developed as part of a study surrounding generic household waste. Through applying a set of industrial and craft techniques, I experimented until the materials simulated natural materials, like stone or wood.

Lightweight yet durable, it allows for such diverse applications as furniture, wall panelling and surfaces for interiors. I’ve made some side tables from flat slates of Bahia Denim and an organic-shaped stool where the material is applied to a curved surface.

Are any of these pieces in production? I sell my Bahia Denim objects through galleries or to museums; they’re currently too expensive to make for a larger production. I do create the material on a bigger scale to be sold as panels, but because it’s such a manual process, it’s quite expensive and retails at almost triple the price of marble. I’m researching how I can improve the process so it can be scaled easily and trying to find the right partners to do this with.

How does living in Berlin inform your work? Berlin is a diverse and open place, and I find it inspirational. It’s relaxed in comparison to other European cities, and more spacious and less expensive, which has allowed me to create bigger work than when I was living in London.

What’s your apartment like? After a nomadic few years, moving back to Berlin has allowed me to set up a home I can fill with items I’ve accumulated: collections from my travels, found objects, gifts from designer friends, anything made of a mysterious material that has a strong personal connection.

I have a turquoise-green cast-aluminium chair by Faye Toogood that’s a reminder of my time in London. In India, I felt drawn towards warmer colours and handmade works, and brought a lot of homeware back — crafted objects with a more primitive aesthetic. These pieces have soul.

Is it tough to survive as a material designer? Europe’s a nice place to be based and I’ve set up a great network; I’m also hoping to do more work in New Zealand and would love to find collaborators and receive bespoke commissions. [In Europe] there’s a lot of interest in new materials from architects and retail designers who want to use more conscious, meaningful and exclusive materials in their spaces. Clients are beginning to understand that these values come with extra costs but allow them to be at the forefront of developments and to stand out.

Developing new materials is costly and can take years. When working with waste, the inconsistency of the material can be tricky; for example, for a new material I’m working on, made from recycled glass, it’s important that all of the glass comes from the same source.

What do you hope for the future? To see more of my materials implemented in spaces and architecture, and to work on bigger-scale projects. It’d be great to save a huge amount of waste material from ending up in landfill and to really have an impact. I see the objects I make as communicators that carry ideas in the form of a product. They’re nice pieces that tell a cohesive material narrative.

sophierowley.com

Words Claire McCall

Photography David Born