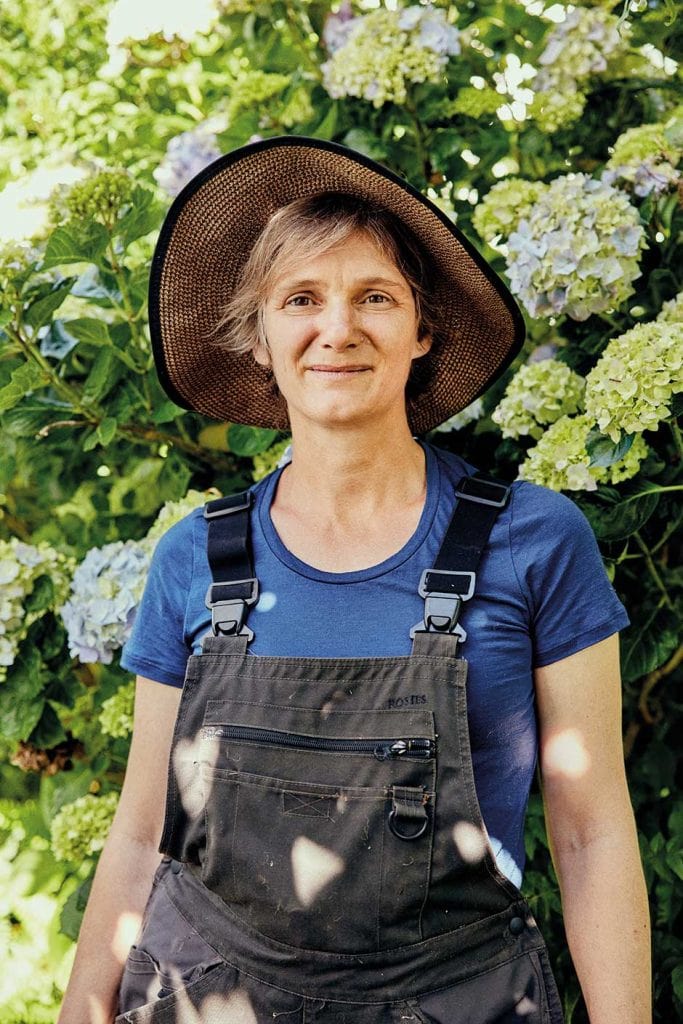

In a nutshell, Katrina Wolff helps people optimise their gardens, placing an emphasis on healthy soil via biodynamic methods. She reckons we’re close to a tipping point at which composting — aka making soil from waste — will be considered cool, and as far as she’s concerned, it’s an integral part of any successful plot, a skill with a status equivalent to that of growing food and flowers. With the guidance of the consultations, online school, workshops and workplace classes she offers through her business Blue Borage, her customers are quickly able to cancel their garden-waste-collection services and put their compost and weeds to good use.

So you call yourself a ‘soilpreneur’…? The term came about as a play on the words ‘solopreneur’, and ‘soulpreneur’ — I’m all three! In many ways, Blue Borage is carving out a new niche; there are tradespeople for all sorts of property-maintenance jobs, but on the whole, garden-maintenance contractors don’t know a lot about composting. Biodynamic composting is a specialised skill crucial for biodynamic winegrowers and market gardeners, but the scale of their work doesn’t easily translate to the home garden setting, so that’s where Blue Borage comes in to devise bespoke composting systems to suit individual home gardeners.

As well as your own website, people can look you up on Tradespeople’s directory of women and gender-diverse tradies — what can they expect if they hire you? Everyone I talk to is interested in growing healthy food and finding natural ways to deal with challenges such as weeds and pests. I like using what’s already in place to design a system that typically includes biodynamic composting, hot composting, worm farming and fully circular green-waste management.

Some simple biodynamic principles are about caring for all living beings as part of our ecosystem, be they bees, birds, chickens, worms, slugs or snails; fostering biodiversity by planting different types of plants in the same space; increasing soil health so the soil can feed the plants; and careful observation of challenges, to explore the possible root causes and apply preventative treatments that build plant resilience.

Why do you do what you do? Soil health is connected to human health through the food we eat, but my work is about so much more than just food. It’s also about helping people connect with the outdoor spaces surrounding their homes, and localising more of the daily services we depend on for social wellbeing.

Compost has strong associations with waste management and is often seen as rubbish. This has to change, and Blue Borage is about linking compost to flowers, bees and food. Compost is to gardening what flour is to baking, and it’s time to start making top-quality compost an accessible choice for everyone.

What has this work taught you? That people need to start their gardening journey where they feel comfortable. It might be a punnet of microgreens followed by a tray of salad greens — slowly gaining the confidence to grow a little more each season.

I’ve also learned that composting is addictive. It’s like a modern form of alchemy that captures the imagination of people of all ages. I’ll never forget the seven-year-old who looked at the compost we made from his school’s green waste with amazement and said, “That’s not compost — that’s soil!”

Why should we all be getting our hands dirty? Holding a handful of really good compost feels a bit like going for a walk in the forest, with a sense of abundant life. It’s quite literally a grounding experience to plant a garden, even a small one — your skin wants that connection with the earth.

For me, a secondary reason that compost is so important is that it’s a chance for so much of our ‘waste’ to be given a new life and be elevated to something of immense value in our food system. I often see scientific reports forecasting that globally we’re going to run out of topsoil for growing food. Whether that happens in 60 years, 100 years or 200 years, the fact is that every time someone puts food scraps into a kitchen disposal unit, that’s a little bit of nature that isn’t going to be used to make compost.

To me, if we really wanted to care for the environment, our cities would have effective, clean, well-run composting and worm-farming operations within walking distance of every home and workplace. I feel like

we need a new compost story in New Zealand, something to connect people to the soil that grows their food. This new narrative probably won’t come from the current experts, so I wonder what would happen if musicians, artists, designers and craftspeople took up the challenge of redefining compost. What might be possible?

blueborage.co.nz; tradespeople.co

Interview Emma Kaniuk

Photography Frances Carter