The door to multidisciplinary artist Areez Katki’s home away from home in Mumbai, India is a portal to a whole lot more.

On a surface level, it was work that took artist Areez Katki from his home in Auckland to his ancestral home in Mumbai last year, after receiving a grant to carry out a residency and project. But that was just the tip of the iceberg.

So Areez, what does home mean to you? I’ve been moving around so much in

the past decade that I have to question what ‘home’ entails. Perhaps it’s an amalgamation of places within oneself that aren’t limited to one physical site. Auckland is where my immediate family lives and where I often return to between travel-related endeavours to replenish on time spent with whanau, by the sea, at my Parnell studio and revisiting sites from my childhood in East Auckland. However, it isn’t quite so easy to sustain a practice in that setting, being so isolated from certain resources in the northern hemisphere and tethered to my genetic heritage, so by luck I also happen to have an apartment in Mumbai on the top floor of a 100-year-old art deco building. It’s where I was born and my mother, her parents and parents’ parents lived, but no one lives there anymore, so I have space, solitude and autonomy there, which to me, as a 29-year-old Kiwi who will probably never own property in Auckland, is the definition of luxury. I’m very grateful.

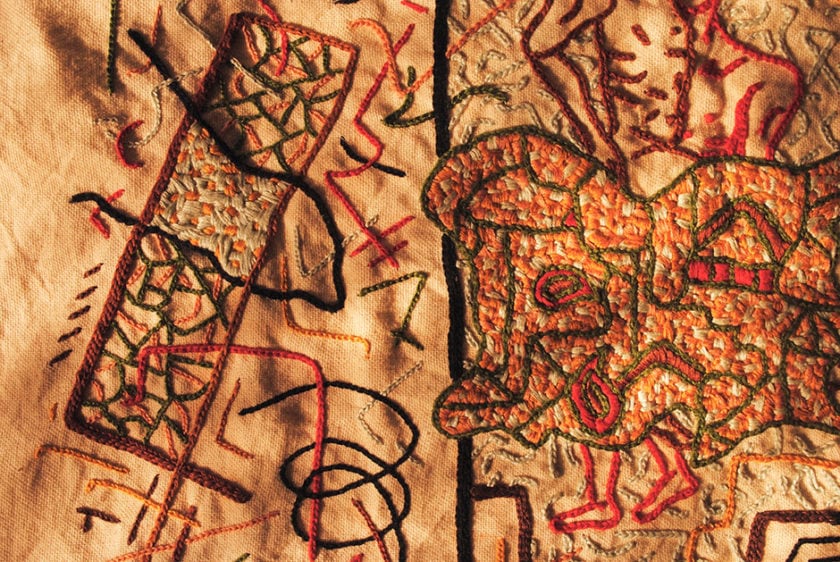

Your time in Mumbai led to your first solo show, which uses textiles to explore your Parsi history… The formulation of my exhibition Bildungsroman follows the narrative trope of revisiting one’s origin story. Being the son of immigrants who were raised in India then moved around a lot resulted in me having both Parsi and Kiwi identities to consolidate, along with being queer. Before last year, there was so much about me that had been conveniently ‘abridged’ in order to make this identity more comprehensible for my peers and romantic partners, and palatable for an audience. One then realises far too late in life that this is a highly problematic way to live, hence my attempt to consolidate such affairs that deal with identity, spirituality and sexuality through an exploration of my heritage, which I can now proudly trace back across 5000 years. During and since Bildungsroman, the pride that I’m finally able to have around both my sexuality and ethno-cultural identity has been immense. Such endeavours are extremely healing and I deeply wish this for all individuals, particularly those who stem from diasporic whakapapa.

What does Bildungsroman examine? It looks at two narratives, framed by craft materiality in the domestic realm. One is an autobiographical narrative and coming-of-age inspection of my identity as a self-removed Zoroastrian who then returns to the setting of his birth to examine the ethno-religious properties of his heritage and consolidate two opposing aspects of his identity: queer and Zoroastrian. This led to a celebration of the female divinities that had long been kept suppressed by religious practices, also aided by queer, feminist and revolutionary figures from the Parsi community. The second narrative is a wider survey of the cultural heritage, history and archeology that directly led to the dispersion of Zoroastrians around the world, raising questions around survival, the retention of knowledge, spiritual practices and an overall resilience to entering mainstream world religions.

What else was special about spending time in Mumbai? My neighbours and the stories they shared about what life was like before I was born. My great-grandmother taught our neighbour Aunt Dolly, who’s also my grandmother’s bestie, to weave torans, then over half a century later, she taught me. To inherit knowledge and document oral herstories was the most special part of this experience for me.

What daily rituals did you enjoy there? If I was up before there were too many people on the street for my voice to carry, I’d put on my robe and yell “Narial-pani walla, ek please!”, which translates as “Coconut-water man, one please!” from my bedroom window, send a basket down three storeys with some cash in it, and wait for it to be replaced with deliciously creamy fresh coconut for breakfast.

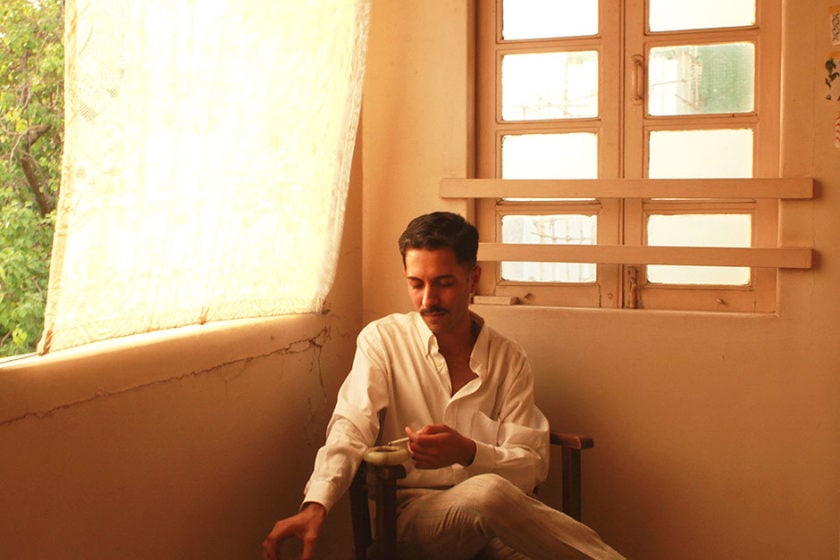

I’d also make espresso in an old Bialetti stovetop coffee maker and sip it on the balcony with the birds while feeding them seeds, day-old bread and peanuts. This is something that my grandmother always did and continues to do in Auckland every morning.

I loved working in my corner studio at my grandfather’s teak desk with its pale blue laminated surface, where I wrote, read, formulated and made watercolour renderings/studies to examine and research what then went towards my textile panels. My larger embroidered works were executed in a bigger living room that was converted into another studio space filled with my books, tapestry frames, hoops, collected textiles and equipment that I tried to organise in little ceramic vessels. This was where most works were physically executed, from either an old Chandigarh armchair or my grandmother’s daybed.

Another ritual was my late-afternoon Campari spritz around golden hour, a dreamy part of the day. This was something I usually did after work, often with guests while we sat on the balcony smoking Gold Leaf cigarettes, listening to music and watching people on the street below.

Areez Katki is represented by Tim Melville Gallery, see more of his work here.

areezkatki.co

Interview Alice Lines

Photography Areez Katki & Ashish Shah